Marketing Misfires

Shelly Jain, Elizabeth Stearns and Dan Turner offer 15 classic, cautionary cases of failed marketing campaigns

If the best-laid plans of marketers often go awry, just imagine what happens to the worst-laid plans.

The history of marketing is littered with botches and blunders at every stage of the new product process, from value creation to value capture. For the sake of argument, we asked three of the University of Washington Foster School’s marketing faculty—associate professor Shailendra Jain and senior lecturers Elizabeth Stearns and Daniel Turner—to share their favorite cautionary tales.

Value CREATION

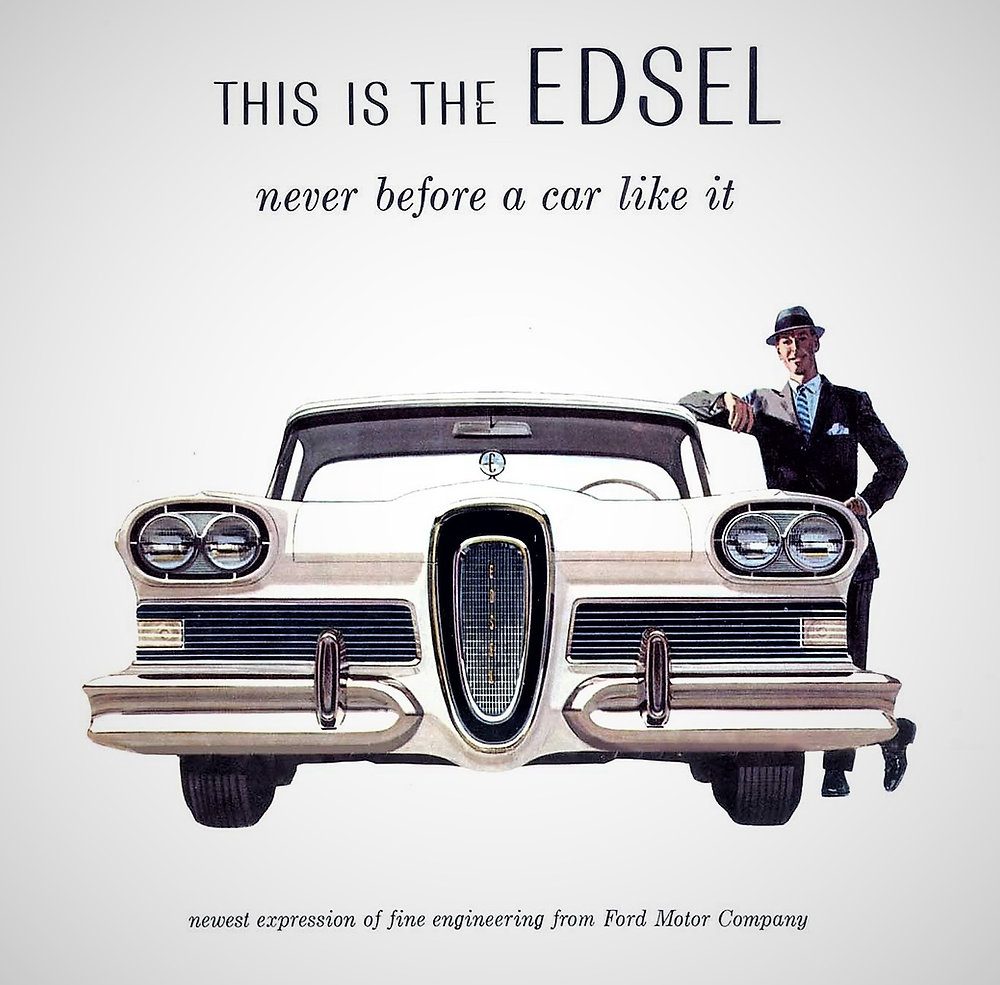

The modern era of marketing failures began with the Edsel, the Ford Motor Company’s heavily hyped car, a revolution in style and technology that hit the marketplace in 1957 with a thud.

Offering unique value that the customer wants, it turns out, is fundamental but far from a given.

New Coke

In 1985, Coca-Cola revamped its famous secret formula to counteract growing competition from Pepsi, which had stolen a chunk of its dominant market share. The sweeter New Coke beat both its original formula and Pepsi in blind taste tests. But when New Coke supplanted old, loyalists revolted. Coca-Cola ended the experiment quickly. Its brilliant comeback with Coke Classic not only recovered lost market share, but gained additional ground.

“In a naïve way, it made perfect sense for Coca-Cola to improve its product, making up for a known deficiency versus a focal competitor,” Turner says. “But it made a fundamental error in forgetting what value it was offering customers—brand associations of America, friendship, nostalgia. These are emotional associations we cannot ignore.”

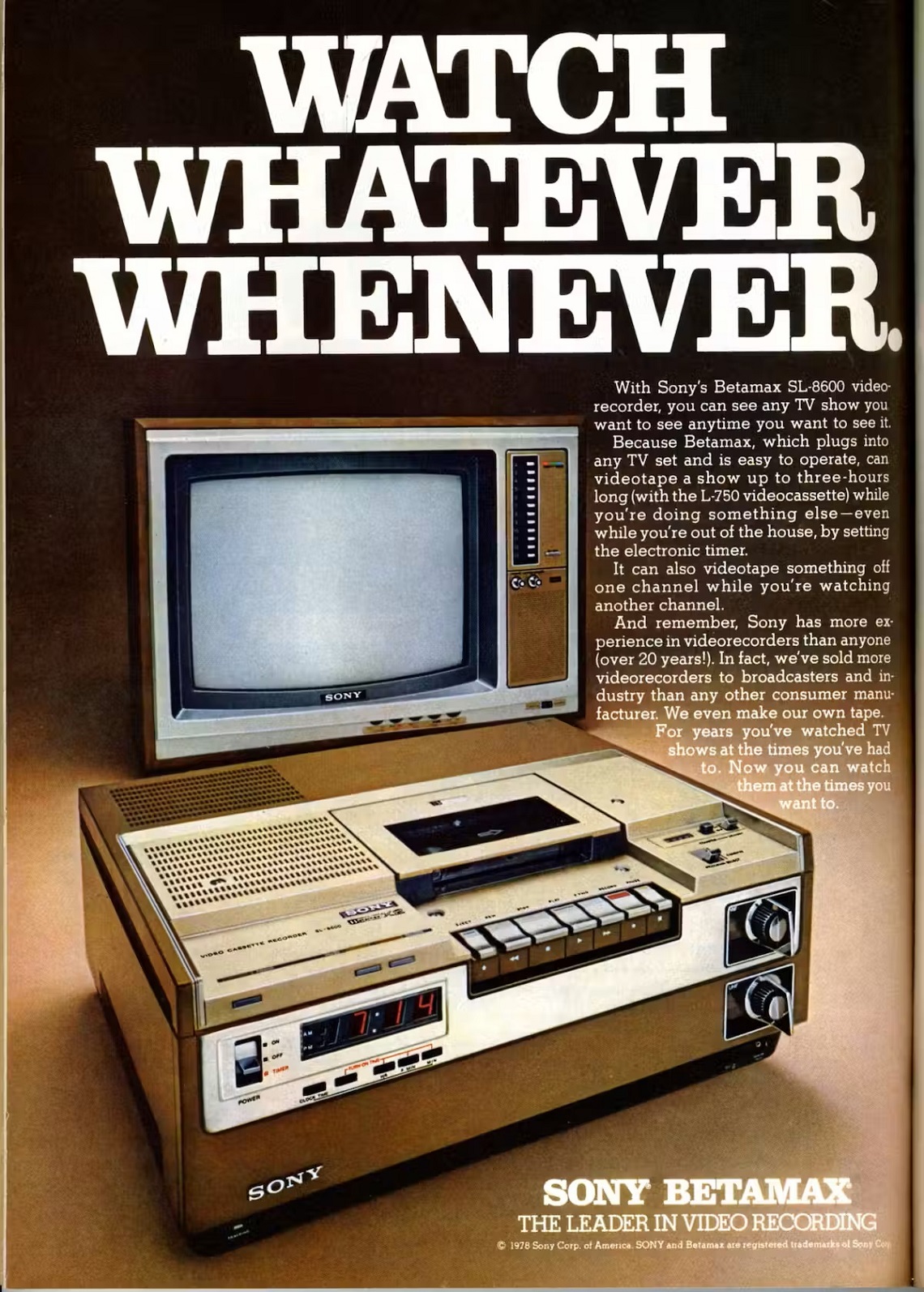

Sony Betamax

Sony was first on the market with a home videocassette player/recorder in 1975. Its Betamax boasted better picture and sound quality and a smaller console, but a shorter recording time than JVC’s competing VHS technology, which arrived two years later. But while Sony attempted to dictate the industry standard, JVC recognized that consumers liked the added tape time, and opened its technology to multiple companies, quickly creating massive market dominance.

“Sony had a strong brand, but it could not do battle with 30 or 40 companies that jumped on the VHS bandwagon,” Jain says. “Once a technology is introduced and adopted widely, it becomes very difficult to dislodge.”

Honda Accord Hybrid

While the Toyota Prius has become an emblem of fuel economy and environmental responsibility, the similar class Honda Accord Hybrid barely registered with consumers during its brief existence from 2005-07. The hybrid version of the popular Accord offered more power but no greater fuel economy, and cost $9,000 more. While other car companies rolled out successful hybrids, Honda quickly cut its losses.

“There is a limit to the strength of a brand,” Jain says. “Honda failed to provide a utilitarian benefit—greater fuel economy—or a self-expressive benefit—a sense of doing something for the environment—that a hybrid customer demands to justify the premium price.”

Value COMMUNICATION

Ad campaigns, like hair styles and fashion trends, can look ridiculous in retrospect. But they also can do serious damage to a brand, as when a Xerox commercial from the 1960s memorably demonstrated that its new office copier was so easy to operate that a monkey could do it, enraging legions of secretaries.

From the illustrious history of modern marketing, here are some other notable failures to communicate:

Nike

Though Nike has created some of the most inspirational messaging in marketing history—“Just do it,” anyone?—it’s also responsible for some egregious overreaches. Most horrifying may have been a 2000 commercial in which elite runner Suzie Favor-Hamilton and her speedy Nike kicks outsprinted an eventually winded chainsaw-wielding maniac. The punch line: “Why Sport? You’ll live longer.” Amid predictable protest, the ad was quickly pulled.

“Throughout history marketers have made a plethora of mistakes in trying to capture and hold the attention of target customers long enough to deliver a marketing message,” Turner says. “Nike is a company that I greatly admire, but it has consistently pushed beyond the envelope in trying to convey its message.”

Toilet to Tap

That’s not a spectacularly bad product name, but rather the cheeky media-branding of an innovative wastewater-reclamation project in Orange County, California.

In a region that pipes in 90 percent of its water from the Colorado River—at enormous cost—the process has been somewhat successful for irrigation uses, but thus far failed to convince the public of its drinking potential.

Meanwhile, Singapore’s Public Utilities Board has turned purified sewage into a popular branded bottled product called NEWater, and demonstrated its safety by showing the nation’s president sipping it happily.

Meanwhile, Singapore’s Public Utilities Board has turned purified sewage into a popular branded bottled product called NEWater, and demonstrated its safety by showing the nation’s president sipping it happily.

“Reclaimed water is a good idea—it’s not a question of if but when we will adopt it,” Stearns says. “But in California, its marketing has been taken over by the consuming public. They haven’t figured out how to overcome the psychological barrier, the ‘yuck’ factor.”

SunChips

You may have heard about the new compostable SunChips bag. Or, perhaps just as likely, you’ve actually heard the bag, an absolute ear-sore according to rampant press reports.

In introducing its innovative, sustainable packaging, Frito Lay failed to demonstrate its value and muffle the critics. And company engineers raced to create a lower-volume compostable package, at great cost, which has just hit the domestic market.

In introducing its innovative, sustainable packaging, Frito Lay failed to demonstrate its value and muffle the critics. And company engineers raced to create a lower-volume compostable package, at great cost, which has just hit the domestic market.

“Unlike Sun Chips Canada, which stuck with the original packaging after successfully showing the actual composting of the product to reinforce its value,” Stearns says, “Sun Chips USA pulled all but its base brand, succumbing to critics.”

Vespa

A stealth marketing campaign employed attractive actors to ride Vespa scooters up to restaurants, cafes and bars, flirt with customers and hand out their phone numbers—which turned out to connect them to the local Vespa dealership. Bait. And. Switch.

“A great example of an ill-conceived value communication gone horribly wrong,” says Turner.

Groupon

The unique online coupon service had enjoyed mostly positive buzz until it aired a brazenly insensitive commercial during the 2011 Super Bowl that misappropriated the plight of the Tibetan people to sell its service. The public cried foul. Groupon pulled the ad and tumbled into damage control.

“You don’t always have to like an ad campaign, but your market segment does,” says Stearns. “This ad was in such bad taste that it begs the question: who at the agency and/or company approved it?”

Diet Pepsi

The new Diet Pepsi “Skinny Can” is tall, thin and undeniably elegant. The problem? It debuted during New York Fashion Week, juxtaposed against willowy models and pronounced to be “in celebration of beautiful, confident women.” Critics found nothing to celebrate.

“Pepsi misunderstood the context into which they introduced the product,” Stearns says. “They did not foresee the charges of irresponsibility in an environment where obesity and eating disorders are so prevalent.”

Value CAPTURE

Execution and pricing gaffs may appear less spectacular than product or promotion misfires, but they can prove even more tragic. A good product or a good promotion—or both—can be shot down by a bad business model, or even just a myopic one.

EMI CT Scanner

The breakthrough medical imaging device was invented and introduced in the 1970s by Electrical and Musical Industries (EMI), a company better known for recording the Beatles.

EMI’s adventure in medical hardware was an outlandish success for a few years and the company made a quick fortune. But it didn’t understand the market, or what the competition would bring. Without deep enough pockets to innovate, EMI was quickly overwhelmed by GE and other large players in the CT scanner gold rush.

EMI’s adventure in medical hardware was an outlandish success for a few years and the company made a quick fortune. But it didn’t understand the market, or what the competition would bring. Without deep enough pockets to innovate, EMI was quickly overwhelmed by GE and other large players in the CT scanner gold rush.

“Technology is a moving target,” explains Jain. “You have to constantly be on the cutting edge. If you’ve shown that there’s money to be made and you don’t assume that competitors are already getting into the market, you’re sleeping.”

Laker Airways Skytrain

The original discount airline was a big success in the 1970s, carrying idealistic young people “across the pond” in no-frills flights for low, low cost. But when its charismatic British founder, Sir Freddie Laker, tried to expand into US domestic routes, the monopoly of big American carriers simply matched fares until they choked out the upstart.

“Flying with Freddie Laker—as I did when I was in grad school—was like being part of a movement, supporting an alternative, breaking up the cartel,” says Stearns. “Now it’s a revealing case study on the challenges of expanding in a regulated or monopolistic market.”

Tupperware

In 2004, the iconic food-storage products company began selling its plastic ware in Target stores. But by making Tupperware more accessible, it rendered obsolete the “Tupperware party”—source of 90 percent of company business and an unmatched vehicle for communicating value. Sales fell 17 percent, and Tupperware pulled out of Target within a year.

In 2004, the iconic food-storage products company began selling its plastic ware in Target stores. But by making Tupperware more accessible, it rendered obsolete the “Tupperware party”—source of 90 percent of company business and an unmatched vehicle for communicating value. Sales fell 17 percent, and Tupperware pulled out of Target within a year.

“It’s a great example of incentive misalignment,” Turner says. “The Tupperware chairman and CEO pronounced it big and bold… and ugly.”

Dotcoms

Why the big bubble? The Internet promised a revolutionary business model but, initially, few knew how to make money with it. “Dot-com theory” dictated that an e-business expand its customer base as rapidly as possible, even if doing so meant huge annual losses. Presumably, profits would magically flow later. But for every Amazon and eBay that thrived, hundreds more pioneering dot-coms went down in flames.

Says Turner: “Pets.com, Webvan.com, Kozmo.com and many, many others generated impressive revenue lines but, sadly, failed in a massive collapse of wrong-headed pricing model logic. Poor value capture relegated them to the dustbin of marketing history.”

Read more the on the classic failure of New Coke from Dan Turner, as well as iPhone’s struggles in Asia from Shelly Jain and Elizabeth Stearns on good marketing saving a flawed product—the VW Beetle.