Difference Makers

The Foster School of Business has been shaped by a century of formative, formidable figures. Here are just a few of the most fascinating, across the decades.

1917-1927:

Bright light, extinguished too soon

It is perhaps the cruelest footnote of Foster School history that its promising first year in business would end in personal tragedy in the highest office.

University of Washington President Henry Suzzallo appointed a rising star named Carleton Parker to lead the newly formed School of Business Administration in 1917. He wooed Parker away from the University of California, where the young scholar had earned growing acclaim for his engaging teaching of economics, his introduction of psychology into the discipline, and his preternatural ability as a labor negotiator.

During the first year of America’s involvement in World War I, Parker averted or settled 26 strikes—many during his tenure as dean. He mediated labor disputes for longshoremen, loggers and builders of Camp Lewis. He negotiated an eight-hour workday for forestry workers, and a wage raise for gas employees.

“Parker had the trust and confidence of both sides in disputes between labor and capital,” wrote one colleague. “His services were called in whenever trouble was brewing… Thanks to him, strikes were averted; war-work of the most vital importance, threatened by misunderstandings and smoldering discontent, went on.”

At the School of Business Administration, the man the UW Daily dubbed “the Builder” laid a solid foundation for the future. He hand-picked the inaugural faculty, composed of seven distinguished scholars from Harvard, Stanford and Wisconsin.

But in the spring term of his first year in the office, Parker contracted a virulent strain of pneumonia and died March 17, 1918. He was just 39.

“Parker’s sudden death in March shocked the entire university,” reported the UW Tyee.

But the foundation held. In the wake of Parker’s untimely passing, Stephen I. Miller stepped up to take the mantle. Serving as dean for the next five years, Miller led the school through a period of exponential growth—from 12 students in 1917 to 1,350 in 1920. By 1921, the UW College of Business Administration (as it was recast) was one of only 20 schools to be accredited by the AACSB, and considered one of the largest and finest in the land.

1927-1937:

Incidental historian, intentional trailblazer

Ruth Grant Pearson (BA 1925, MBA 1928) wasn’t the first woman to serve on the faculty of the UW School of Business Administration (that distinction goes to firebrand economist Theresa McMahon). But she certainly made a historic impression.

After completing her undergraduate studies in business, Pearson graduated directly to a faculty post, heading the school’s merchandising curriculum from 1926 to 1931. In 1928 she established the prescient Women’s Vocational Club, an organization promoting networking among women professionals working in Seattle’s nascent business community. Dean William E. Cox named it “outstanding project of the year.”

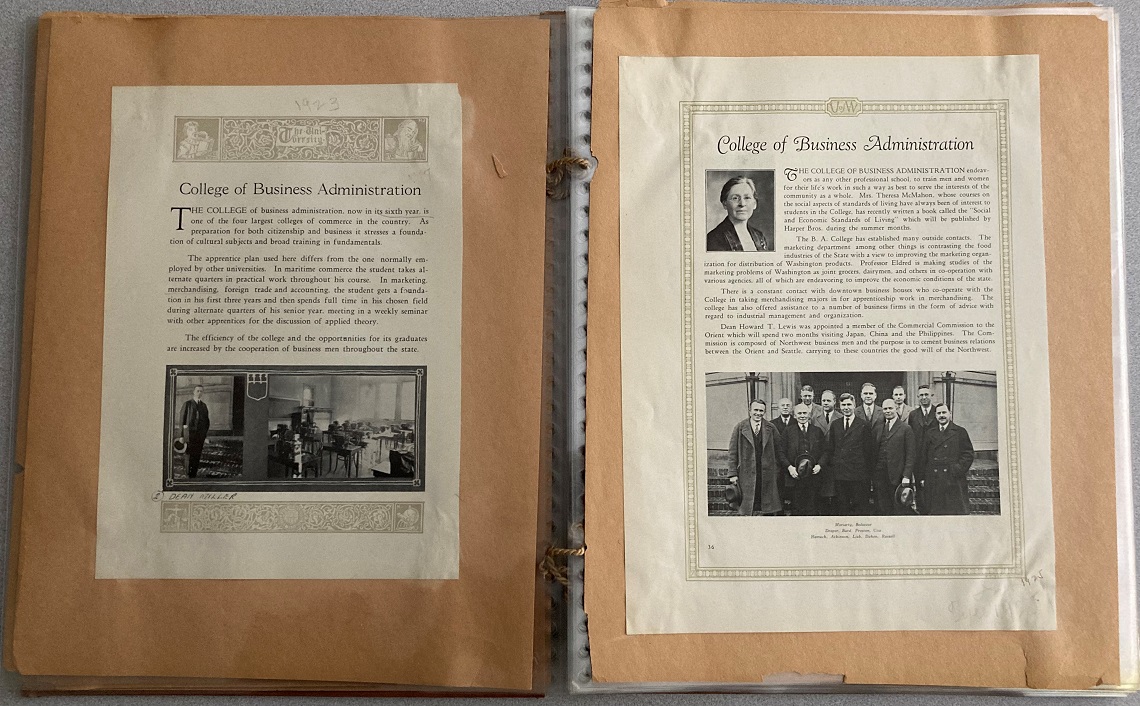

Beyond her role as a founding mother of a school that now educates as many young women as men, Grant Pearson left a more tangible legacy as well: an invaluable scrapbook that was recently unearthed from the basement of Mackenzie Hall.

Composed on the occasion of the school’s golden anniversary, the book is a trove of rare photographs, newspaper clippings and memories—and one of the most tactile touchstones of the Foster School’s rich history.

1937-1947:

A separate peace

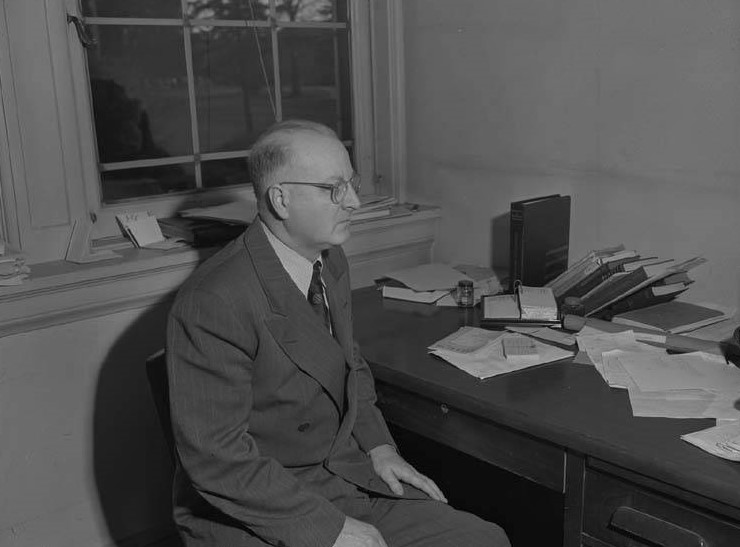

During his tenure as dean from 1938 to 1948, Howard Preston delivered the College of Business Administration through some turbulent times, from the Great Depression to World War II and into the Baby Boom. But the most divisive conflict under his watch turned out to be internal.

Economics had been part and parcel of the College since its founding. But a tectonic rift was growing between the faculties of economics and business administration. The more theory-based economists wished to return to the College of Arts and Sciences. And the field of business administration was emerging as a distinct discipline, in which the faculty was anxious to assert its independence.

Preston, an economist and expert on banking, favored keeping the two disciplines together. He was an extraordinarily empathetic leader who cared deeply about students—even surreptitiously delivering degrees to graduating Japanese American students who had been banished to internment camps—and faculty.

But the debate grew increasingly rancorous. In one of the final acts of his deanship, Preston brokered a split that led to a more amicable relationship between two complementary faculties.

Moreover, it represented a philosophical shift in the College of Business Administration toward the humanity of enterprise.

Donald Mackenzie, a professor of accounting who led the committee charged with exploring the dissolution, wrote that “business is not simply the application of economic theory” and that members of the business administration faculty preferred to offer an education based not on “cold economics but on human welfare.”

Mackenzie argued that business leaders who recognize their workers as “human beings and not ‘economic men’ have proved to be the most successful in the world.”

The field of business, he concluded, could “contribute much more to the social welfare than economic theory has contributed. If we teach our business courses purely from the viewpoint of profit, and not from the viewpoint of society, we should be thrown out of the university.”

1947-1957:

Age of enlightenment

The Foster School of Business today employs one of the elite research faculties in the world, regularly ranking among the most prolific producers of groundbreaking knowledge that is published in the most influential journals of each discipline.

It wasn’t always so.

Early business professors were called, first and foremost, to teach. The extent of their scholarly production, if any, was most often the writing of textbooks for classroom digestion.

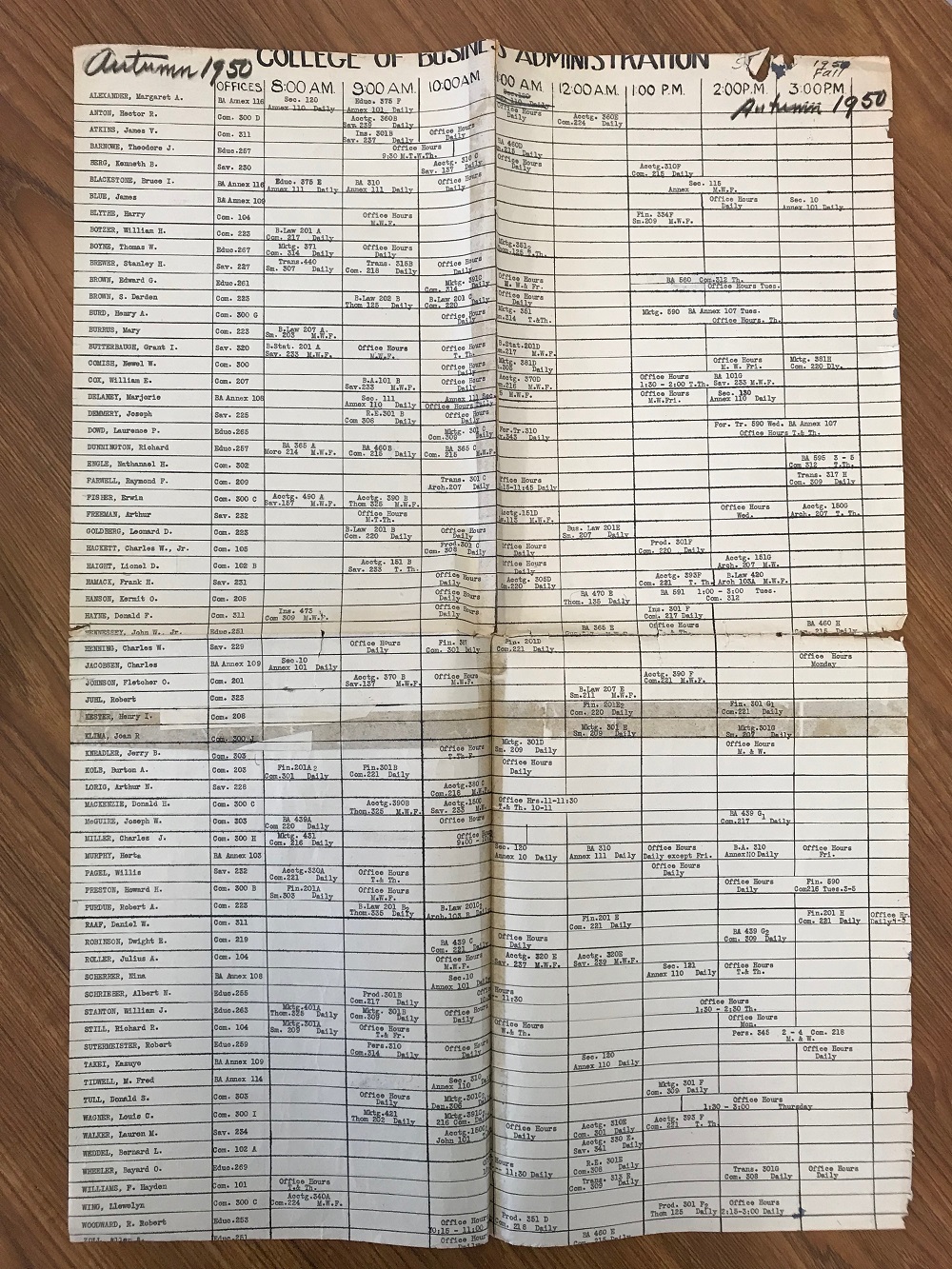

This orientation expanded significantly with the installation of Austin Grimshaw as dean of the College of Business Administration in 1949. A dynamic innovator with experience in business enterprise, Grimshaw led a revolution in management education at the UW. He moved the curriculum toward the tools of management and the art of decision making, and increased the focus on the graduate program.

But the Harvard-educated Grimshaw was also an ardent scholar. He came to the UW after a distinguished career at the University of Illinois, one of the most consciously research-oriented public universities at the time. And perhaps his most indelible legacy at the UW was to push scholarly research to the forefront of faculty priorities for the first time. He also established a doctoral program to educate the next generations of scholar-educators.

This new call to scholarship did not resound with everyone. Some faculty even staged a “mini-revolt.” But midway through his tenure, Grimshaw found a powerful intellectual champion in President Charles Odegaard who endeavored to build one of the world’s elite research engines at the UW.

Grimshaw’s advances paid dividends. By the time he stepped down in 1963, business had returned to its standing as the most popular major on campus.

1957-1967:

Forging alliances

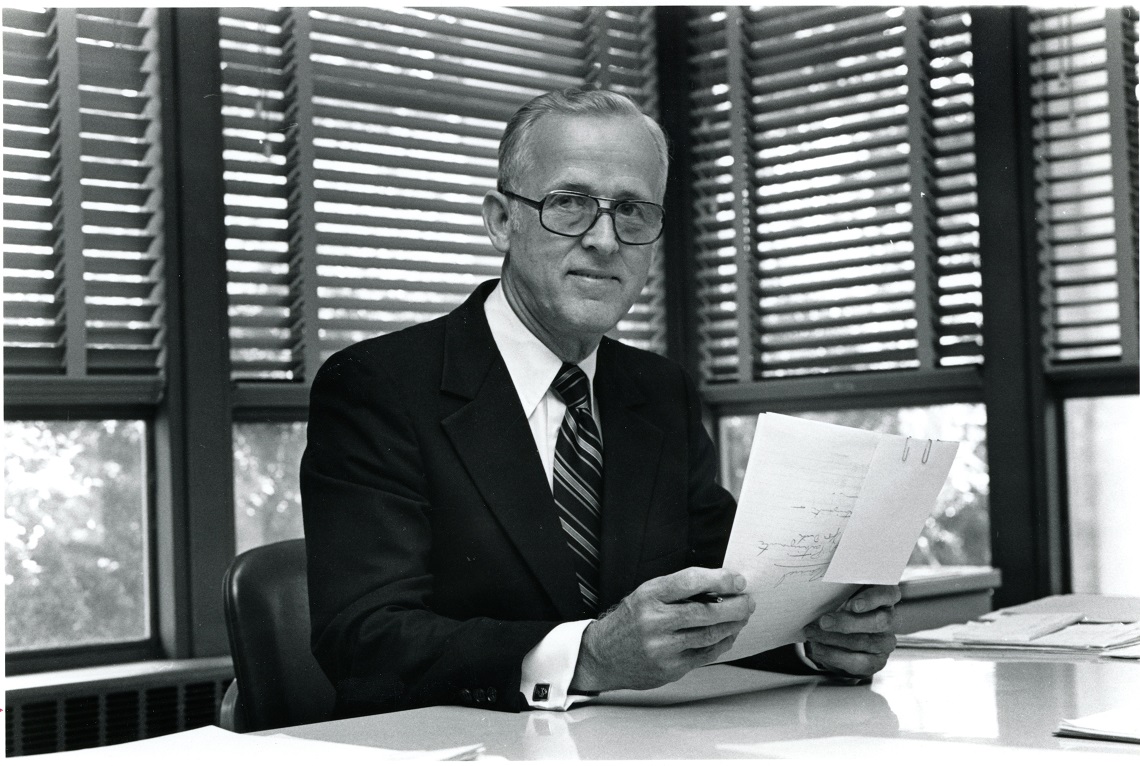

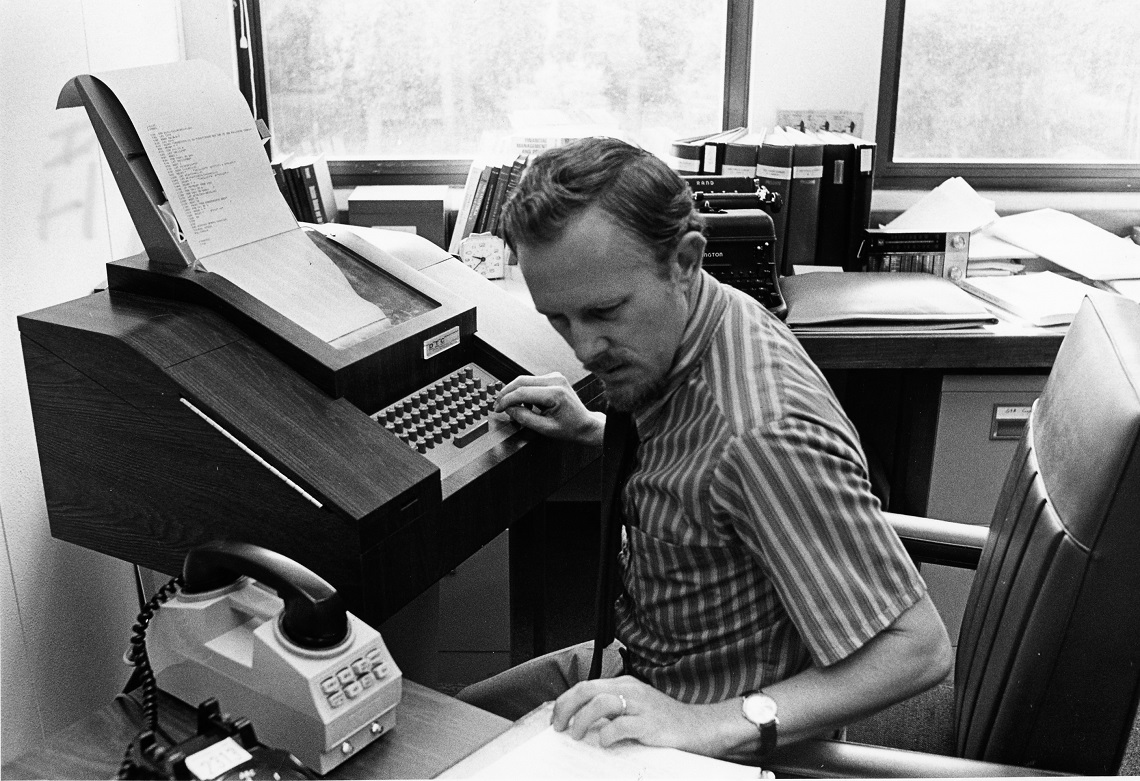

Dean Kermit Hanson introduced numerous innovations during his eventful 15 years at the helm of the College of Business Administration that spanned 1964 to 1981.

Among them, Hanson modernized the curriculum, spun out a distinct Graduate School of Business Administration, advanced executive education offerings, developed a computer center, and recruited and fostered exceptional scholars such as William Sharpe, the Nobel Prize-winning financial economist, Fred Fiedler, a giant in industrial and organizational psychology, and Gerhard Mueller, the “father of international accounting.”

To make business education more relevant and responsive to market demands, Hanson strengthened ties with the business community, assembled a formal Business Advisory Board, and recruited a related Affiliate Program to secure invaluable private and corporate support for the school into the future.

In short, Hanson modeled a thoroughly modern business school.

“Looking to the future in this age of increasingly rapid change, American industry, if it is to maintain its position of world leadership, should devote more attention to research and innovation, sophisticated techniques of management, and economic growth and the external environments,” he wrote in an early and prescient report to faculty. “Similarly, graduate schools of business must be in the forefront in research related to business and the economy, and in the utilization of research in a constant renewal of a curriculum designed to prepare students for managerial careers. The importance of teaching and curriculum development cannot be overemphasized; we must preserve the status of teaching concurrently with our encouragement of research and consulting activities. It is essential that faculty develop curricula for executives who seek greater proficiency in the art and science of management by enrollment in special programs and seminars. The computer, strategic planning, information systems, environmental forces, and the multinational dimension of business are among a host of subjects of immediate and specific concern.

“Both American business and American education for business have large stakes in preparing future business leaders and in seeking new knowledge and techniques.”

Kind of sounds like a roadmap to the Foster School today.

1967-1976:

Seeding entrepreneurial studies

In 1970, Professor Karl Vesper got the green light to create and deliver the School of Business Administration’s first course in entrepreneurship. “That’s back when people would ask, how do you spell that?” Vesper recalls.

He had come to the UW with a joint appointment in engineering and business, armed with a Harvard MBA and a Stanford PhD in mechanical engineering—and an idea, perhaps a bit ahead of its time, to join the two disciplines in an effort to commercializing innovation.

First, though, the course. Vesper had written entrepreneurial case studies at Harvard, but never taught the subject. So he reached out to schools that had, in an effort to glean some intel on course design. He came to realize that precious few were actually teaching entrepreneurship.

But Vesper culled a set of best practices from that original exchange of curricula, and disseminated them to anyone who was interested in an “open source” experiment.

As entrepreneurial activity took off around the development of new technologies through the 1970s and ’80s, Vesper’s influence grew. To establish credibility for entrepreneurship as a field of academic study, he organized the first entrepreneurship research conference while visiting Babson College. A few years later he established the Entrepreneurship Division of the Academy of Management.

Businessweek and Inc. both named Vesper the “dean of entrepreneurial studies.”

For his part, Vesper considers himself more of a Johnny Appleseed than a Ben Franklin, a cross-pollinator rather than a founding father. And he’s amazed at what entrepreneurship has become, both professionally and academically. Entrepreneurship courses, programs and centers—such as the Foster School’s own highly ranked Buerk Center for Entrepreneurship—have proliferated around the world.

“I’m awed by the amount of activity there is today,” he says. “You’d think that somebody must have planned all of this. It ain’t so. I just thought it was a fun subject.”

1977-1987:

Shattering glass ceilings

When Nancy Jacob was named the ninth dean of the UW School of Business Administration in 1981, she became the first woman to lead a major American business school. But hers was no overnight ascension.

As an undergraduate at the UW, Jacob (BA 1967) worked as a research assistant to Nobel Prize-winning financial economist William Sharpe, eventually co-authoring an early book on the economics of computing. She earned her PhD in financial economics at UC-Irvine and became one of a select few women teaching finance at the university level. In 1978 she became chair of the UW Department of Finance, Business Economics and Quantitative Methods.

And during her tenure as dean (1981-1988), Jacob introduced the Executive MBA Program, centers for banking and retail management, and the Business Education Opportunity Program, formed to promote economic, ethnic and gender diversity and increase enrollment and support of underrepresented students.

Jacob’s leadership was emblematic of the growing diversification of the school. William Bradford, one of three academics enshrined in the Minority Business Hall of Fame, became Foster’s first Black dean in 1994, his decades of groundbreaking research in minority business development catalyzing the Consulting and Business Development Center.

And Yash Gupta became the school’s first South Asian American dean in 1999, bringing entrepreneurial thinking and ambition for the reinvigoration of the curriculum around technology and the construction of world-class facilities.

When Jacob was honored with the Foster School’s 2014 Distinguished Leadership Award for her influence on the school and the two successful investment firms she subsequently founded, Jacobs reflected on the journey. “We make a big deal of the glass ceiling for women executives,” she said. “But that’s misleading because life is not a vertical climb. It’s a multidimensional trip. It doesn’t come with an easy button or a fair button. It is what it is. But when one door closes, another opens. You have to be flexible and you have to be willing to deal with adversity.”

1987-1997:

Centers of attention

The early ’90s in the Northwest were best known for great coffee, groundbreaking software and grunge rock. But this fervid era of creation also produced a trio of game-changing centers at the UW Business School. More than academic think tanks, these centers were designed to challenge students with indelible, real-world learning experiences.

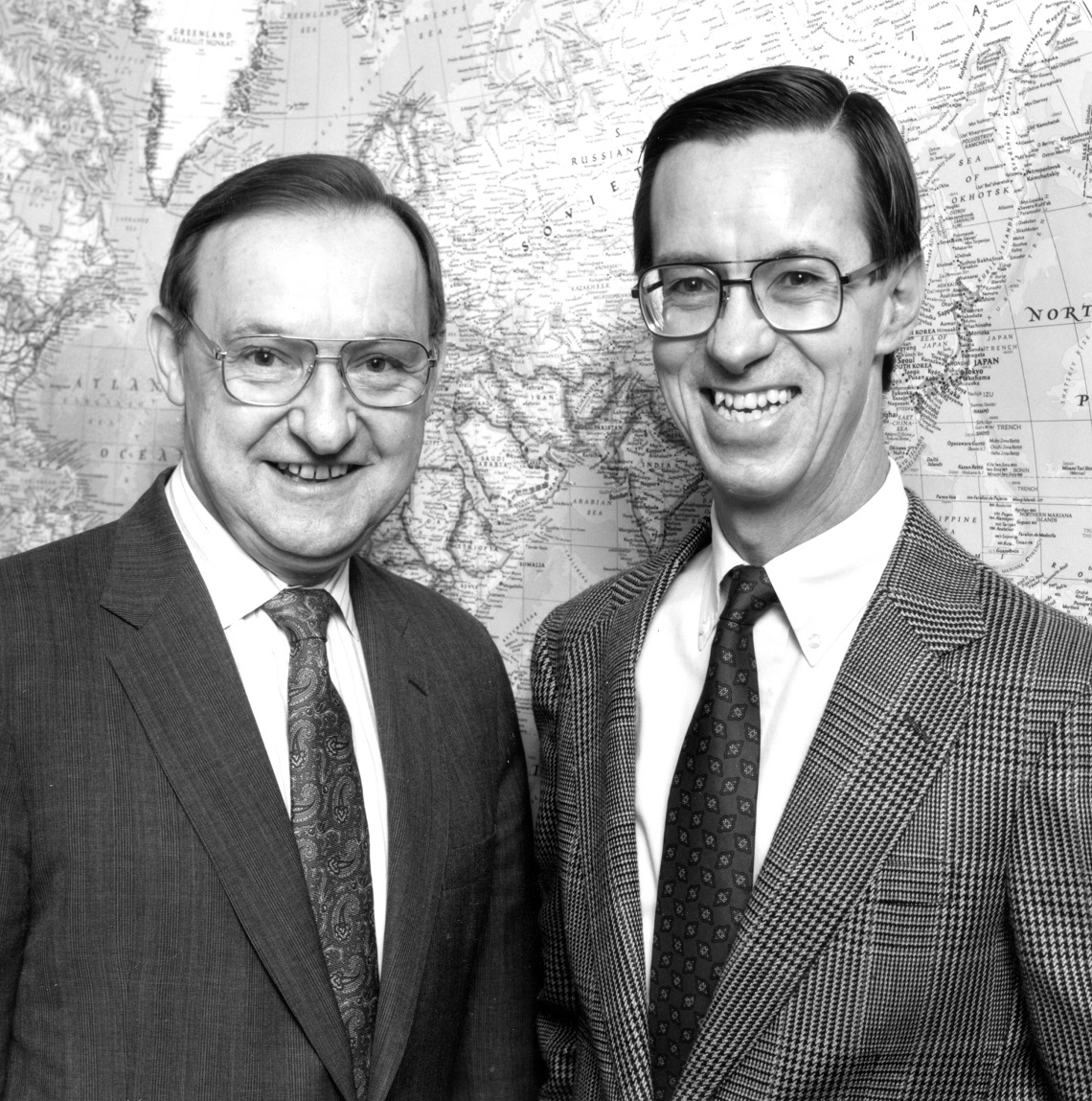

First up was the UW Center for International Business Education and Research (CIBER), funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Education and founded in 1990 by Professors Gerhardt Mueller (executive director) and Richard Moxon (faculty director), both longtime advocates for international business education and study. The renamed Global Business Center has become a bustling hub of international activity at the Foster School. More than 300 Foster students study abroad through its programs, and another 500 students annually benefit from its global business case competitions. Graduates from global certificate programs are working all over the world.

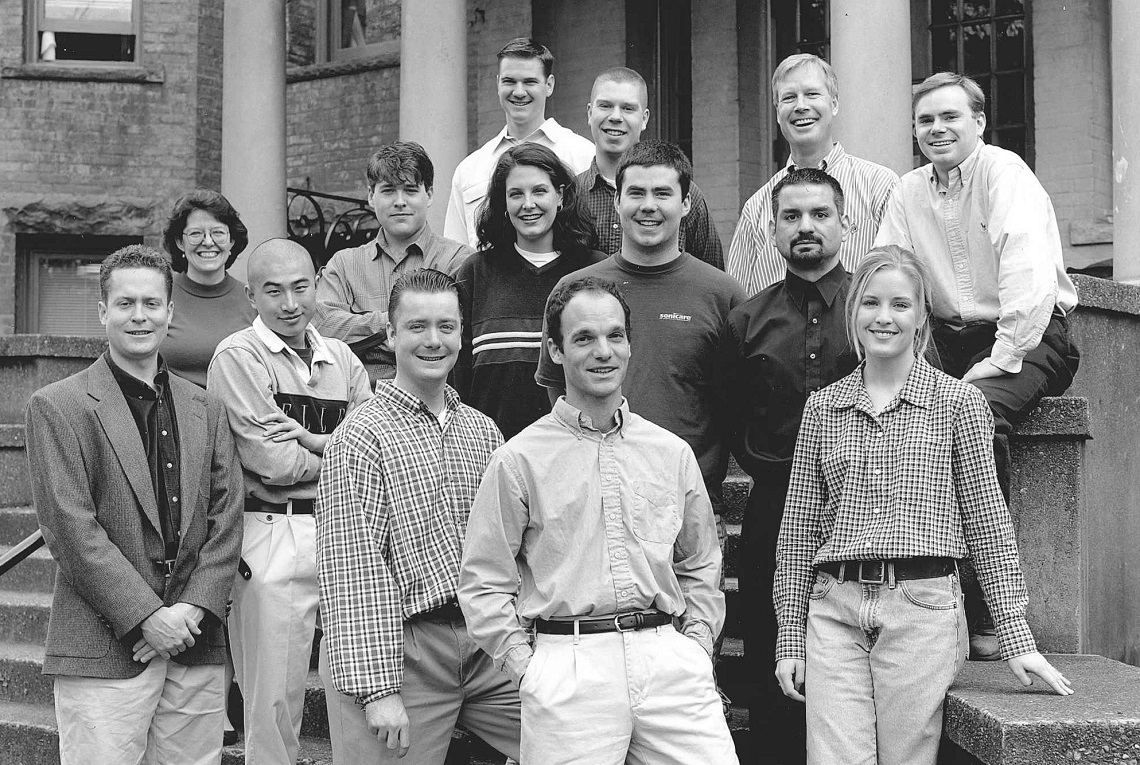

In 1991, the Program in Entrepreneurship and Innovation was launched by Professors Gary Hansen and Borje “Bud” Saxberg with venture capitalist Neal Dempsey (BA 1964). The renamed Arthur W. Buerk Center for Entrepreneurship has lived up to the promise of its title, continually spinning out new ventures from the marquee Dempsey Startup Competition (formerly the Business Plan Competition) to the Alaska Airlines Environmental Innovation Challenge to the Hollomon Health Innovation Challenge to the Jones + Foster Accelerator to the Startup Job Fair to certificate programs and the new Master of Science in Entrepreneurship. Bottom line: at least 987 startups have been founded by Buerk Center and competition alumni, raising nearly $400 million in funding.

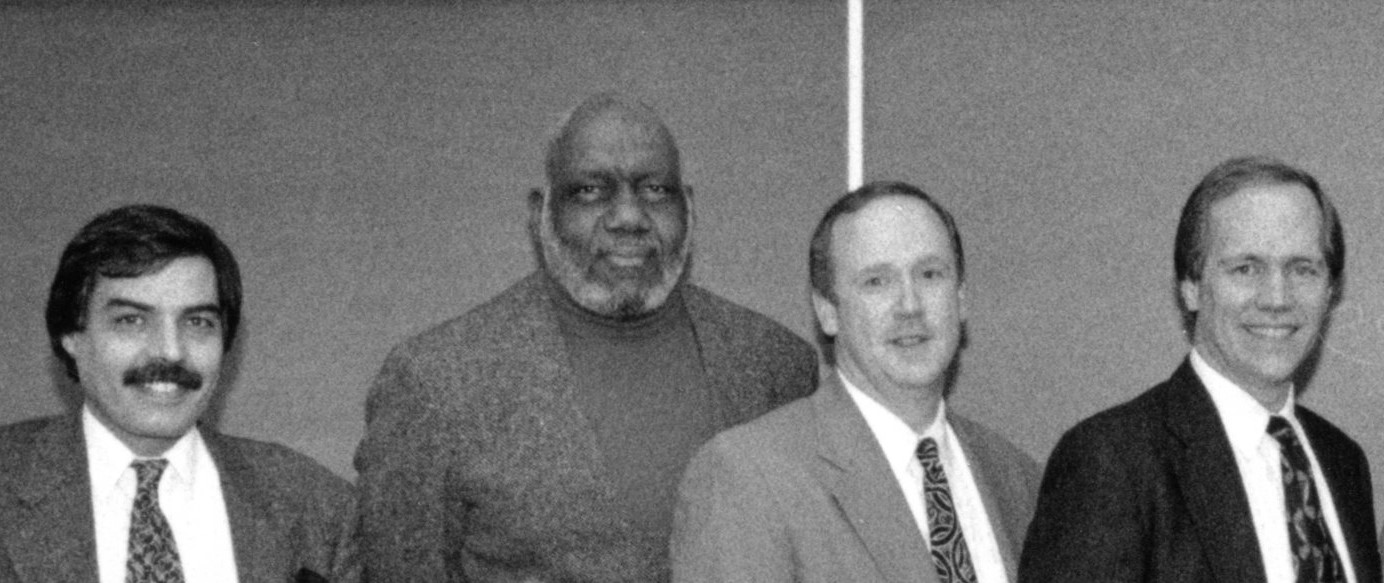

And in 1995, graduating MBAs Michael Verchot and Paul Pressley partnered with Professor Thaddeus Spratlen to establish the Business and Economic Development Program, inspired by the practicum work of Professors Spratlen, David Gautschi, and Ali Tarhouni and the research of Dean William Bradford. Today’s Consulting and Business Development Center has expanded to provide a range of educational and—student-driven—consulting assistance to small businesses with the goal of spurring economic growth in distressed communities across the state. Its vital work has resulted in more than $150 million in new revenue generated and more than 125,000 jobs created and retained.

1997-2007:

A new, familiar name

As an honorary eponym for an academic institution, you could hardly do better than “Foster.”

It’s a name, richly symbolic, that evokes that noble promotion of human development. And, in a happy bit of fortune, it also happens to be the surname of a family that has done more financially than any other to further business education at the University of Washington.

The legacy begins with Albert O. Foster (BA 1928), who founded the investment firm of Foster & Marshall, Seattle’s first locally-owned brokerage to own a seat on the New York Stock Exchange. He and his wife Evelyn, a fellow UW graduate, were also leading figures in the cultural life of the city.

Their son, Michael G. Foster, departed the UW early to start his own career in finance and eventually returned to Seattle to join his father’s firm. After becoming president in 1971, he surrounded himself with a dedicated, talented team and set a clear direction of aggressive expansion, becoming a regional finance powerhouse before brokering the sale of Foster & Marshall to Shearson/American Express in 1982.

Michael, A.O. and Evelyn Foster established The Foster Foundation in 1984. It has supported the school’s facilities, libraries and student scholarships ever since.

In 2007, the UW Business School was officially renamed the Michael G. Foster School of Business, in recognition of a combined $50 million in giving from The Foster Foundation.

The man behind the moniker was known for his brilliance with numbers and his remarkable timing and strategy, as well as impeccable ethical standards. But he also was known as a man who never sought the spotlight, who gave generously of himself to family, friends and the community, and who led by example for generations to come.

2007-2017:

World-class campus

After Commerce Hall opened its doors for the School of Business Administration’s debut in 1917, the school didn’t have a new dedicated building until 1960 and the construction of Mackenzie Hall. This new headquarters of the school’s faculty and administration, named for influential accounting professor Donald Mackenzie, was designed by Paul Hayden Kirk, one of Seattle’s most influential modernist architects.

Two years later, Balmer Hall went up across the lane, adding a dedicated classroom building of complementary design. Named after prominent local businessman and UW regent Thomas Balmer, the four-story, 80,000-square-foot classroom building was built for $1.7 million. The “unadorned example of modernist architecture” hosted generations of students—many who fondly (or not so fondly) remember their days in “Balmer High”—until its razing in 2010.

Balmer was never intended as a 50-year solution for a fast-growing school. In the early 1970s, plans were commissioned envisioning a soaring architectural showpiece between Denny and Balmer Halls. But those were not great days to indulge in lofty dreams.

The Foster Library and Bank of America Executive Education Center opened in 1997. But it wasn’t until the early 2000s that renewed energy revived the plan for a world-class HQ for the school.

PACCAR Hall was the product of nearly $80 million in private support, championed by Dean Jim Jiambalvo and Campaign UW co-chairs Neal Dempsey, Ed Fritzky and Mike Garvey, and capped by an extraordinary naming gift from the PACCAR Foundation and the Pigott family.

Two years later, on the site of dearly departed Balmer Hall, rose Dempsey Hall, a modern companion to PACCAR. These LEED gold, architectural award winners foster collaboration by their very design.

But the Foster campus is not quite complete. A top priority of the UW’s current “Be Boundless” philanthropic campaign is raising funds to construct a modern replacement, at long last, for Mackenzie Hall.