A Penny, Saved

How Robert Khoo transformed an obscure gaming comic strip called Penny Arcade into a veritable media empire

As a business model, Penny Arcade appears dunderheaded at best and doomed at worst.

It’s an old-school paneled comic strip on the Internet, irreverent to a fault and ripe with riffs on video gaming subculture, in-jokes incomprehensible to all but devout readers, flippant critiques of substandard games and stinging verbal jabs at industry gentry. Which would be fine, except that it’s supported by advertising sales to that same gentry—the Nintendos, the Electronic Arts, the Sonys, the Microsofts—sometimes skewered by the comic’s game-obsessed antiheroes. Oh, and one more thing: the company only accepts ads for games it deems worthy. (Talk about biting the hand that feeds you.)

Yet Robert Khoo (BA 2000), Penny Arcade’s president, has somehow turned this imbroglio into a clever, focused media empire. And he’s made the comic’s offbeat creators into veritable tastemakers to the $40 billion digital game industry.

In the blood

Khoo is a gamer, almost from birth. He was raised in Portland and weaned on the seminal video games of Atari and Odyssey. An uncle from Japan introduced him to the original Nintendo Entertainment System (then called Famicom) years before it was available in the United States. “I’ve been playing games all my life,” he says.

But Khoo also possessed a mind for business. He enrolled in the Foster School with hopes to marry his two passions and honed his entrepreneurial chops in the UW Business Plan Competition. But after graduating with a 3.98 GPA into the dot-com bust, he put entrepreneurial dreams on hold and applied for any job at Nintendo. “I didn’t care whether it was game testing or janitorial,” he says. “That was the space I wanted to be in.”

When Nintendo didn’t call, he settled for a position at a small strategy consulting firm that worked with early-stage technology start-ups and foreign companies looking to break into the US market.

The pitch

While representing a Korean game developer with American dreams, Khoo thought of this popular little Web comic he knew called Penny Arcade. He got a meeting with founders Mike Krahulik and Jerry Holkins and proceeded to pitch them an advertising partnership with his client. It did not take long to learn that Penny Arcade was not really a business at all.

“It was just two guys who created this great comic out of their apartment,” Khoo recalls. “Their main revenue stream was donations from readers. They set their drive limits on how much they needed to pay rent and groceries. They had accidentally signed away the company twice already, and gotten it back by sheer luck. In the first 15 minutes, I realized they had no idea what they were doing.”

Penny Arcade’s readership was already impressive and impassioned. And growing like kudzu. But given the voodoo economics of the enterprise, day jobs were looking inevitable.

“I was shocked,” Khoo says, “because here was what I believed to be an amazing product that these guys put out— they should be millionaires.”

It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. And Khoo pounced. He drew up a 50-page business plan for Penny Arcade, then called a second meeting with the founders to discuss a less modest proposal: “I said, ‘Here’s the deal. This business plan is yours, no matter what. But I would love to execute it myself. I have the market experience, and I’m a gamer so I definitely understand the space. You give me the green light and I will quit my job and work for you for free for two months. If I can pay for myself after two months, great, keep me. And if I can’t, cut me.’

“That’s an offer you can’t refuse. Especially if you’re two guys barely making a living working out of your apartment.”

A twisted model

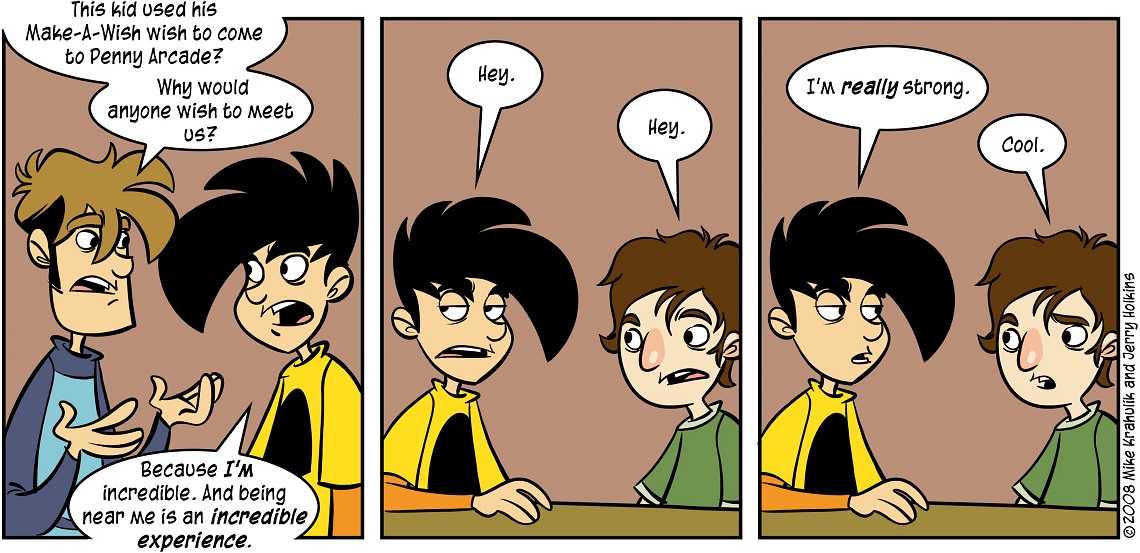

The protagonists of Penny Arcade are Gabe and Tycho, stylized alter egos of creators Krahulik and Holkins. Their characters are boldly rendered in a style that hints of Japanese Manga. But what makes Penny Arcade so resonant to ardent gamers is what the characters say, and how they say it. Their idiosyncratic humor, their candor-at-all-cost is impeccably delivered in the peculiar, fertilized vernacular of the audience. All of this has earned Penny Arcade a personal connection with readers, “people who don’t see gaming as a hobby so much as a lifestyle,” Khoo explains. A subculture of a subculture.

As it turns out, that subculture is pretty big, and getting bigger. Penny Arcade counts 3.5 million readers scattered across the US and the English-speaking world, and nearly 70 million page views a month. It’s now one of the top five game sites on the Web.

Even in the early days, Khoo found plenty of clout to work with. His business plan began with renouncing the charity model and introducing market rates for ad sales. But there was a major twist.

“Advertising and editorial have always gone hand-in-hand. But we decided early on that we would change that model,” Khoo explains. “Instead of making the editorial advertising, we make the advertising editorial: No ads appear on Penny Arcade unless we like that game.”

Until advertisers got wise to the deal, Penny Arcade was actually turning down three times the revenue it was making. What appeared to be short-sighted lunacy, though, has proved to be long-term brilliance. This unorthodox (suicidal?) ad policy demonstrated to exacting readers that the spirit of Penny Arcade lives beyond the pixels. It meant genuine indie cred, that can’t be bought. “It’s what keeps our brand strong,” Khoo surmises. “We’ve been able to grow without losing our authenticity and integrity that the voice has always had.”

Community at the center

With the aberrant advertising model as foundation for the business, Khoo was free to stretch Penny Arcade in many directions. Its primary product is content, supported by advertising. Exactly what every media company does. “What differentiates us is this amazing community, and everything branches off of that,” he says. “We’ve become the central hub for hard-core gamers.”

On the customer side, that means studying the “business of Garfield and Peanuts” to leverage the Penny Arcade brand into apparel, merchandise, syndication, book publishing and collectible cards. On the industry side, it means selling creative consulting to developers like Ubisoft and Vivendi, and organizations like the game-rating ESRB. “Mike and Jerry are guys whose opinion the gaming industry really looks up to,” Khoo says. “We knew that had to be worth something.”

Perhaps the ultimate manifestation of Khoo’s community-building is PAX (Penny Arcade Expo), the company’s annual convention. In just five years, PAX has become the nation’s largest convocation of gamers, a heady mash-up of trade show and cultural phenomenon. This year Khoo, with a staff of 10 and hundreds of volunteers, orchestrated the harmonic convergence of 58,000 gamers to the Washington State Convention Center in downtown Seattle, in what has been described as a kind of e-Woodstock.

PAX was not in the original business plan. “You couldn’t have anticipated this,” he says. “It started with a fan gathering and has turned into something much larger than anyone could have imagined.”

A trail of spurned suitors

In the media business, there exists what can only be called The Economic Paradox of Cool: The cooler the product, the more popular it becomes; the more popular the product, the less cool it becomes. But Khoo has found a way to traverse the razor’s edge without getting nicked. Now very much a serious business, Penny Arcade remains both cool and popular. As a result, it has also drawn the fervid attention of the gaming industry’s largest suitors.

To follow the logic of what has made the company successful, Khoo can only say no.

“Pretty much any media company you can think of has made an offer to buy us off or buy us out,” Khoo says. “It just won’t happen. There are too many things we couldn’t do if we were part of News Corp or Viacom. I’m not sure there’s enough money in the world worth ruining the day-to-day experience and the amazing impact on this industry and culture that we’re so passionate about.

“We like games. We like having fun. Our biggest fear is becoming corporate.”

Riskier business

There’s nothing remotely corporate about Penny Arcade’s bachelor-pad headquarters, tucked inside a utilitarian strip mall in Seattle’s Northgate neighborhood. Khoo’s office is decked with the geeked-out spoils of gamer celebrity, except for two contiguous walls that are dominated by ceiling-high white boards thick with penned-in plans. It’s going to be a busy year.

Penny Arcade is launching its own video game, a move perhaps as inevitable as it is dangerous for such outspoken critics of the genre. The concept: Gabe and Tycho, set in the 1920s, solving dark sci-fi mysteries in a serialized arc of episodes. The game is being produced by Hothead Games in Vancouver, but tightly controlled by Penny Arcade.

In concert with its premiere, Khoo has unveiled Greenhouse, an online digital distribution platform for games that are Penny Arcade-produced or Penny Arcade-approved—from both blockbuster developers and tiny niche firms that rarely find much of an audience. “A lot of people see us as the one source they trust,” Khoo says. “Not only do we do everything we can to maintain that trust, but also to grow it. That includes providing our readers with compelling new games to check out.”

The white board is awash in additional scribbles that Khoo will make happen in the coming months and years. As in that second meeting, he plans to see how far he can take this company. “By no means have I mastered this beast,” he says, in true gamer fashion. “There’s going to be a lot on my plate for a long time.”

Child’s Play

Penny Arcade is no longer run like a charity, but it does run a charity. Child’s Play has become the largest in the gaming world, raising more than $1 million in 2007—primarily from the vast community of readers—to provide games and toys to 55 children’s hospitals worldwide. “Being in a hospital can be a terrible experience for a kid,” Khoo says. “We founded this fund to try to make the experience just a little more tolerable.”