PNW on a Plate

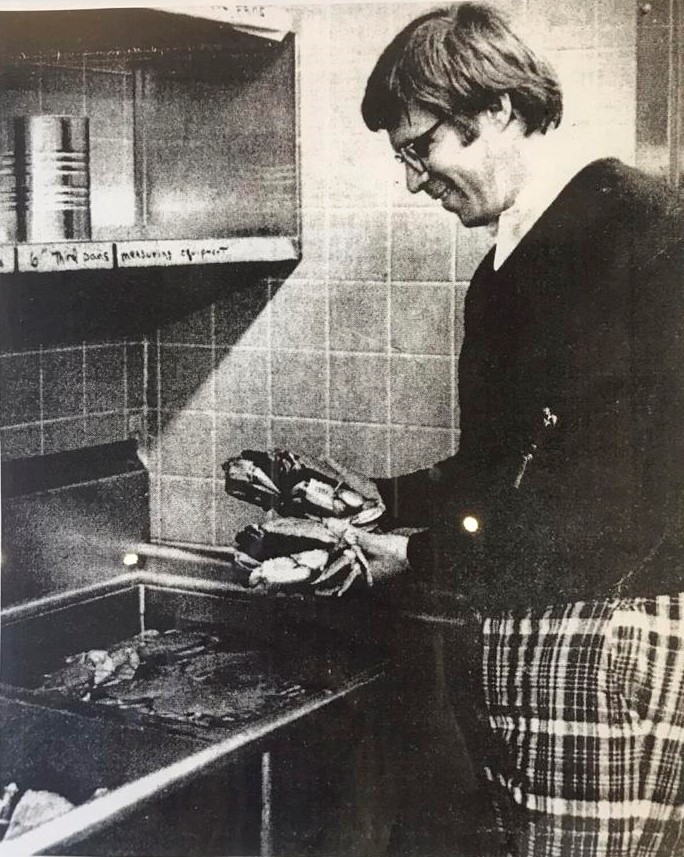

Budd Gould, founder of Anthony's Restaurants, delivers the edible essence of the Pacific Northwest—with a waterfront view

His restaurant empire is 23 strong and growing, an essential presence on virtually every developed waterfront worth mention in the Pacific Northwest.

Yet Budd Gould (BA 1962), the founder and principal owner of Anthony’s Restaurants, is far from the flamboyant restaurateur you might expect to find at the helm of so indomitable a vessel. Gould embodies the easy-going, self-effacing, no-nonsense character of the archetypal Seattle native.

And, not surprisingly, the prominent family of waterfront seafood restaurants he’s cultivated over the past 30 years delivers the quintessence of the Northwest in a meal—the geographic splendor, the laid-back atmosphere and the freshest local delicacies served in season and without pretension, from Copper River salmon, Olympia oysters and Dungeness crab to Yakima asparagus, Walla Walla sweet onions and Cascadian wild blackberries. Throw in a glass of Chateau Ste. Michelle Riesling, and you’ll get the picture in high definition.

“That’s a good way of putting it: Northwest on a plate,” Gould says. “We’re blessed with the quality of seafood and produce and wine we have in this region. So we put that on the plate.”

Trial and error

Not that he was born to the vocation. When Gould was growing up in the 1950s, there really was no restaurant “industry” to speak of, which actually worked in his favor. He had some wild professional oats to sow after graduating from the UW Business School and then earning his MBA from Harvard in 1965. When classmates dispersed to flashy jobs in New York, Boston, Chicago and London, he had other plans. “A couple of us Seattle boys wanted to come back to the Northwest,” he says. “Nobody could understand why.”

Opportunity in provincial Seattle was pretty scarce in those days. Eventually, though, Gould landed a job at Seattle First National Bank, rolling out the state’s first credit card.

But soon he, like many of his contemporaries who went on to shape the modern Northwest economy, got a hankering to start something of his own. With some friends, Gould hatched a string of doomed business plans: a lobster farm; a boat business; a line of pet stores, lodges and hospitals.

“In everyone’s career you’re going to fall down,” he says. “But it makes you cautious; you don’t want to repeat a mistake. You learn from them.”

Learning the restaurant business

And Gould’s next entrepreneurial move was no mistake. In 1968 he and some friends opened a steak and lobster restaurant that survived a Boeing layoff by selling food half-price and cashing unemployment checks in the bar. The economy improved, and a culture of eating out took hold. “We started making money and it started being fun,” Gould says. “I learned the entire business at The Fox, though I was a terrible cocktail waitress and I wasn’t a very good bartender. You could see where this industry was going to go.”

In 1973, Gould opened a second restaurant called Mad Anthony’s, a colonial-themed tavern that served mulled ciders, hearty ales and Baron of Beef plates. He named the cozy, cavernous place after General “Mad” Anthony Wayne, the senior officer in George Washington’s Revolutionary Army. “He was a rogue. A real character,” Gould says, with a laugh. “He would have loved our place.”

Mad Anthony’s was a success from the start. “But it wasn’t on the water,” Gould says.

On the water

“On the water” became a mantra after the overnight success of his third restaurant, Anthony’s HomePort, on the Kirkland waterfront, where it capitalized on the growing seasonal tourism and taste for fresh seafood. “We called it Anthony’s, but no one really got the connection,” Gould says. “So now, years later, we have this family of restaurants and nobody knows who Anthony is.”

Not that he’s complaining. Through cautious, self-financed expansion, Anthony’s archipelago has extended from Bellingham to Spokane to Richland to Bend, Oregon. Except for a restaurant in the new Pacific Market Place at Sea-Tac airport, all of Gould’s eateries sit on the picturesque shore of some body of water, be it sound, sea, lake or river.

Today, Gould shares ownership with family and senior management but remains active in the operations and menu. Anthony’s wholesale seafood business allows the company to ensure quality and reasonable prices. And Gould’s personal connections with vintners, farmers and foragers around the region ensure the richest ingredients.

Like a good neighbor

But good food alone does not make a restaurant a good neighbor. Gould has built loyalty among customers and employees alike. And, following his own commitment to philanthropy, he insists that each location be actively involved in its community. “For some companies, participation in United Way is a way to do this,” he says. “In the restaurant business, we have these great facilities that can be used for fundraising.”

So Anthony’s sites host benefits for environmental organizations, charitable foundations, hospitals and many other causes, raising tens of thousands of dollars in a sitting. That’s more than a meal. And the National Restaurant Association has noticed, honoring Anthony’s with its National Restaurant Neighbor Award in 2003.

But Gould puts more stock in kind words than awards. “I can’t tell you how satisfied I am when I go into a community and see how well Anthony’s is received, or how proud of my crew I am when I hear someone raving about the meal they ate there. That’s why we do this.”

The UW Business School honored Budd Gould with its 2005 Distinguished Leadership Award.