How To Beat Burnout

The right kind of compassion is key to restoring energy and engagement at work

How are you feeling at work these days? Exhausted? Detached? Less effective than usual?

These are all symptoms of burnout.

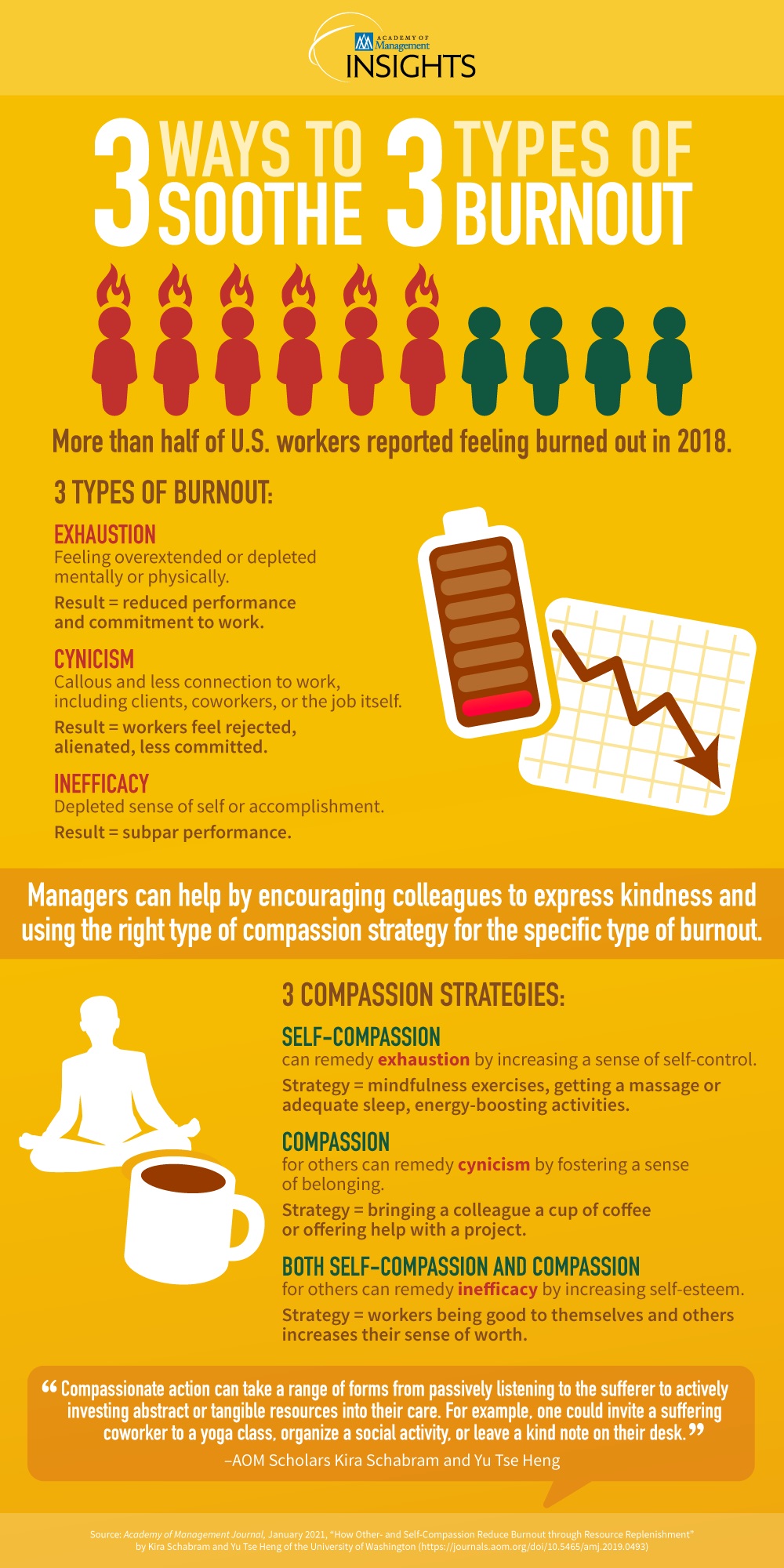

And if you’re feeling one or more of them, you’re far from alone. More than half of American workers reported feeling burned out in a 2018 Gallup poll. And that number has no doubt grown dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic.

But don’t despair. A new study by Kira Schabram and Yu Tse Heng concludes that burnout can be alleviated with compassion—so long as the object and form of compassion aligns with the type of burnout you’re experiencing.

“This finding by no means recuses employers from taking accountability for supporting the mental health of their employees,” says Schabram, an assistant professor of management at the Foster School. “But our research suggests that when you’re feeling burned out, the best person to help you recover may be yourself.”

Burning problem

In 2019, the World Health Organization added burnout to its international classification of diseases that significantly impair health. In the US alone, workplace stress is estimated to cost more than $190 billion in excess healthcare spending and cause 120,000 deaths annually. Its global toll on productivity has been pegged at $1 trillion.

The pandemic has exacerbated the crisis, by dissolving the boundaries between work and home life, intensifying workaholism and erecting barriers between colleagues and clients.

The dilemma can seem impossible to solve. And most conventional remedies are built upon activities that treat those suffering from burnout as the object of their own recovery rather than an active participant.

But what if people took an active role? And exercised compassion as an antidote?

Diagnosing the problem

Schabram and Heng, a doctoral candidate at Foster, set out to answer these questions. They studied social service workers and college students cramming for mid-terms to learn how different acts of compassion affected different kinds of burnout.

They first determined that burnout is not a monolithic affliction. It can present as any combination of three distinct symptoms:

- Exhaustion, which creates feelings of being overextended or depleted mentally or physically, resulting in reduced performance and commitment to work.

- Cynicism, which manifests itself in a callous and diminished connection to work, including clients, coworkers, or the job itself. Workers feel rejected and alienated, which erodes their commitment.

- Inefficacy, which refers to a depleted sense of self or accomplishments, resulting in subpar performance.

They also measured the effect of different acts of compassion—caring for oneself or caring for others—in mitigating these different variants of burnout.

“To recover from burnout,” Schabram says, “you must identify which of these resources has been depleted and take the action best suited to replenishing those resources.”

Exhaustion

When exhaustion is the primary symptom of burnout, the study shows that re-energizing acts of self-care are the most effective means of recovery. These acts can be quite small: taking a brief meditation, cooking yourself a meal, treating yourself to a fancy coffee, even just taking a nap.

“Self-care is not self-indulgent,” Schabram says. “On the contrary, taking a break and focusing on yourself is one of the best ways to combat exhaustion and burnout.”

Cynicism

When burnout presents as detached cynicism, the most effective countermeasure is caring for others. This could mean taking a colleague to lunch, offering words of encouragement, even just listening to someone else’s problems.

“When feeling alienated, focusing on yourself may actually lead you to withdraw further,” Schabram explains. “Whereas being kind to others can help you regain a sense of connectedness and belonging in your community.”

Inefficacy

When burnout means feelings of irrelevance, inefficacy or unproductivity, caring for oneself and caring for others are equally potent countermeasures.

“Acts focused on boosting one’s positive sense of self—which is a byproduct of both compassion for self and compassion for others—proved most impactful in this instance,” Schabram notes.

Start small

Of course, compassionate gestures can be a big ask when you’re already feeling drained.

Observing the actions of social service workers—a population prone to chronic levels of burnout—over three years revealed that those who were already suffering had a harder time engaging in acts of care for themselves or for others. But those who were able to muster the energy to practice compassion showed significant reductions in burnout.

“It’s never too late (or too early) to address your own burnout,” Schabram says. “Compassion is like a muscle: it can be depleted, but it can also be strengthened.”

She adds that studies have shown that compassion meditation training can actually rewire the brain. Breath training, appreciation exercises, yoga and movement practices have also been proven effective tools to cultivate compassion.

“The key is that anyone can learn to be more kind to themselves and to others,” she says. “These small acts—alongside other mental health practices—can help you begin to break free of burnout.”

Set the tone

While it’s reassuring to know there is a straightforward and effective therapy for burnout, Schabram points out that prevention is the best medicine.

It is on organizations and managers to foster a work culture that is not conducive to burnout—and to empower employees to cope in appropriate ways when they experience exhaustion, detachment or feelings of inefficacy.

“Real recovery comes when managers give employees the space to pursue their own restorative opportunities—whether that’s explicitly encouraging them to take personal time to check in with a co-worker, providing resources to build a mentoring network, or even just showing by example that the organization values self-care,” Schabram says.

That said, no matter how much effort an organization puts into combating burnout, there will always be a need for employees to understand where their burnout is coming from and to develop strategies to help pull themselves out.

“Through self-reflection, employees can begin to identify the sources of their burnout, and then proactively determine the actions they can take that will be most effective for their recovery,” she says, “whether that’s self-compassion, acts of kindness or some combination of the two.”

“How Other- and Self-Compassion Reduce Burnout through Resource Replenishment” is forthcoming in the Academy of Management Journal. Kira Schabram has twice been named a favorite business professor by Poets & Quants and is a recipient of the UW Distinguished Teaching Award.

Bottom Line on Burnout

- Burnout manifests in three distinct symptoms: exhaustion, cynicism and inefficacy.

- Caring for yourself can reduce exhaustion.

- Caring for others can reduce cynicism.

- Both forms of compassion can reduce the impact of inefficacy.

- Either form of compassion is difficult to practice when suffering from burnout.

- But small gestures make a big difference toward recovery.