Bonds of Steel

Through the proud Korean firm KISWIRE, three generations of the Hong family connect the modern world

There is a certain industrial artistry in both process and product.

Calliope strains of a Beethoven arpeggio flutter among the clamor of hard-working machinery that reverberates across an immaculate KISWIRE factory floor. Raw carbon steel from colossal spools laces through a gauntlet of precision devices. It is scoured of rust and bathed in acid, lubricated, galvanized, super-heated and drawn through dies of narrowing diameter. And at the end of this elaborate metallic pasta maker emerges a pristine strand of gleaming steel wire.

Elegant, yes. But also essential.

High-carbon steel wire is an indispensible ingredient of civilization. And the kind produced by Korea-based KISWIRE is the best in the business. From filaments finer than a human hair to braided wire rope as thick as an elephant’s trunk, KISWIRE—quietly, reliably—supports bridges, buildings and stadiums, hoists elevators, cranes and oil rigs, reinforces radial tires and high-pressure hoses, transports electricity and telecommunications, fabricates semiconductors, facilitates renewable energy, even gives a piano its dulcet voice.

It also inhabits Scott Hong’s (MBA 2008) past, present and future.

After earning his MBA at the University of Washington Foster School of Business, Scott joined the company founded by his grandfather, and currently led by his father. As production manager of KISWIRE’s Korean operations, Scott is learning the ropes from both elders in preparation to someday take the helm. For the first time, three generations of the Hong family are in business together, a succession of wisdom that has long guided this astonishingly successful company and endowed it with such economic, social and historic significance to the nation it calls home.

“Tradition,” says Scott, “means everything to us.”

Into an Asian tiger

In 1945, a young man named Suk-Cheon Hong was working as a chandler for a Japanese import company, selling supplies to ships docked in the southeast Korean port city of Busan, when his world turned upside down. As World War II came to an end, the Japanese were evicted from Korea, their colony for decades. And Korea, an agrarian society with little industry of its own, was cast into economic chaos.

Suk-Cheon saw opportunity. He started his own maritime supply business, importing goods from Japan. His trade miraculously eluded the advancing communists during the Korean War. But this period of national upheaval made him consider what his company could do for his country. “After the war I decided that I could make money either importing or exporting,” Hong recalls. “But if I exported, it would lift the Korean economy.”

He identified one of his best-selling products—steel wire—and painstakingly learned how to make it. Taking advantage of post-war foreign aid and scraping together modest financing, Suk-Cheon launched the Korea Iron and Steel Wire Company in 1961. Its initial product was aptly named “Elephant Wire” for its strength and dependability.

From the ground floor of his nation’s late-arriving industrial revolution, Suk-Cheon’s gaze was always upward. By 1971, the newly named KISWIRE hit its production goal of 1,000 metric tons a month.

That same year, Suk-Cheon Hong welcomed his son, Young-Chul Hong, to the company. Young-Chul started out creating standards in the production facility. But he rose quickly, right alongside KISWIRE’s soaring fortunes. Through the next decades, the company steadily opened new factories and diversified its product line as the market warranted. Its sales expanded globally, from Korea to Vietnam, Europe, the United States, Japan and China.

Young-Chul ascended to CEO in 1988 and chairman in 2001, as his father gradually eased out of day-to-day operations and into his eternal role as honorary chairman. Now in his 90s, Suk-Cheon Hong still works every day, keeping a close eye on his legacy.

Today, as Scott Hong is groomed to take the family business into a third generation, KISWIRE has achieved a level of success that the honorary chairman says was inconceivable at its humble founding. Today, KISWIRE produces nearly one million metric tons of steel wire, cord and rope each year, carving a 10 percent market share of the fragmented $20 billion global industry. Its 4,600 employees operate 19 production facilities—each dedicated to a specific product line—in Korea, China, Malaysia and the US. Nearly three-quarters of its sales are overseas.

KISWIRE is everywhere.

A different kind of company

Such dramatic growth doesn’t happen by accident. From the beginning, the Hong family has led KISWIRE by the kind of unwritten code that holds enormous power when it genuinely permeates the culture of a family business on a global scale: hard work, honesty, integrity.

These simple traits have resulted in the highest quality product, continually improving efficiency and innovation, and sterling relationships with employees and customers alike. They have sustained KISWIRE through decades pockmarked by war, dictatorial rule, financial crisis and political turmoil.

According to Scott, his grandfather set a lasting growth strategy of financing expansion with profit rather than debt. KISWIRE has relied on its own research and development to drive product improvements, cut costs and open new product lines. It has innovated opportunity, recently opening a factory catering to homemakers’ schedules, and another run by retirees not ready to hang up their hats.

Along the way, KISWIRE leadership has inspired in its work force a rarity in modern times: loyalty. During several severe economic shocks, the now honorary chairman and current chairman sacrificed corporate profits to protect every last employee’s job.

That loyalty was repaid. In the early 1990s, when a newly democratized Korea roiled with labor unrest after decades of military rule, KISWIRE workers organized, then pledged that they would never strike. That’s a level of camaraderie between administration and rank-and-file that a library of management books could not achieve.

It’s the KISWIRE gift, embedded deep inside the Hong family DNA. And Scott Hong gets it.

The education of Scott Hong

Scott may have KISWIRE steel in his bones, but he also had options. His father was obliged to join the company at the behest of his grandfather, originally working, eating, even sleeping at the company’s Sooyoung plant (in a small attached apartment he fondly recalls as “the bunker”).

But times have changed in Korea. Young-Chul Hong did his best to encourage his son and expose him to the business. But the decision to join KISWIRE was Scott’s alone. He attended a science and technology high school, studied mechanical engineering in college and considered pursuing an academic career.

In the end, he chose tradition. “This business is my foundation,” Scott says. “I planned everything to prepare me to one day lead this company skillfully.”

It started with two years interning at the world’s foremost steel manufacturers, including KISWIRE’s largest provider, POSCO. And, to complete his business education, Scott traveled around the world to study management at the UW Foster School of Business. It was a choice strongly recommended by Dr. Chan-Jin Kim, a prominent attorney and family friend who earned a PhD in law from the UW in 1972, and resoundingly endorsed by both grandfather and father.

“There were gaps in my knowledge,” Scott says. “My Foster MBA gave me skill at strategy, leadership, marketing and finance that I can connect with my prior knowledge of engineering and computer science, and my familiarity with the steel wire industry. Plus, my experience in Seattle helped me to see business from many different perspectives.”

His father believes it did even more: “The difference in Scott since before his Foster MBA is that he knows the world better, he understands better how people are linked with business.”

The Shingo pear doesn’t fall far from the tree.

Innovating tradition

“Steel is steel,” says Young-Chul Hong. “It was invented 3,500 years ago and the demand has grown ever since.”

That doesn’t mean, he adds, that KISWIRE rests on past success in an industry that has been historically stable. Since introducing a dedicated research and development facility—and through less formal means in earlier years—the company has perpetually worked to carve time and cost from the process, and produced cables of ever increasing tensile strength to meet the voracious demand of a rapidly developing world.

“Most of our research has been in efficiency,” says Young-Chul. “Now the existing steel wire and rope market is nearing saturation. So we will need to develop into new areas that will be important in the future.”

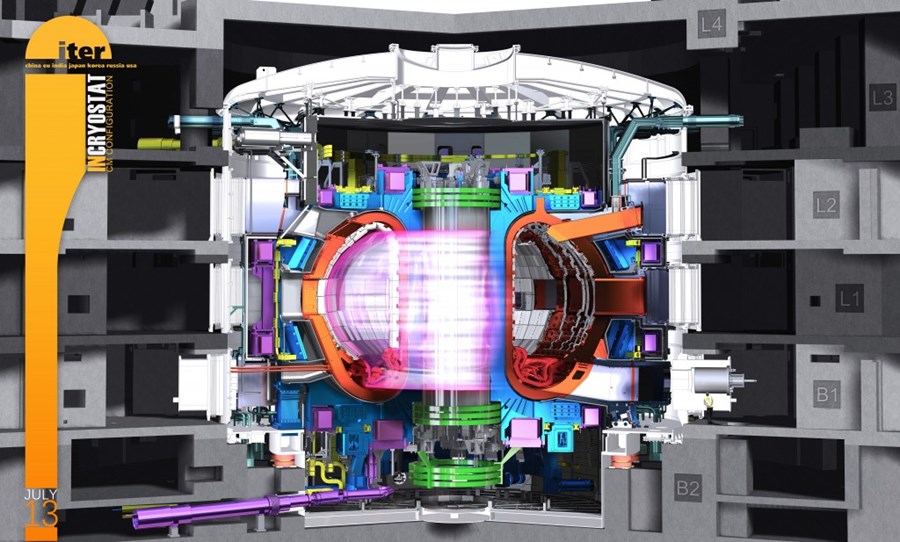

Among the most promising is KISWIRE’s work developing state-of-the-art superconductive wire. It’s a key part of Korea’s contribution to the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER). This much-anticipated nuclear fusion device, under construction in France, is attempting to atomically convert materials in sea water into plasma of 100 million degrees Celsius—an “artificial sun” that could finally solve the planet’s renewable energy conundrum. That sun won’t shine if it can’t be contained and harnessed, requiring superconducting coils that can convey a magnetic field of unimaginable strength. KISWIRE is on it, developing steel that isn’t really just steel.

At this chapter in his family’s history, Scott stands prepared for his future. “If I’m going to follow in the footsteps of my grandfather,” he says, laughing, “I’ll have to work another 60 years at least.”

A family affair

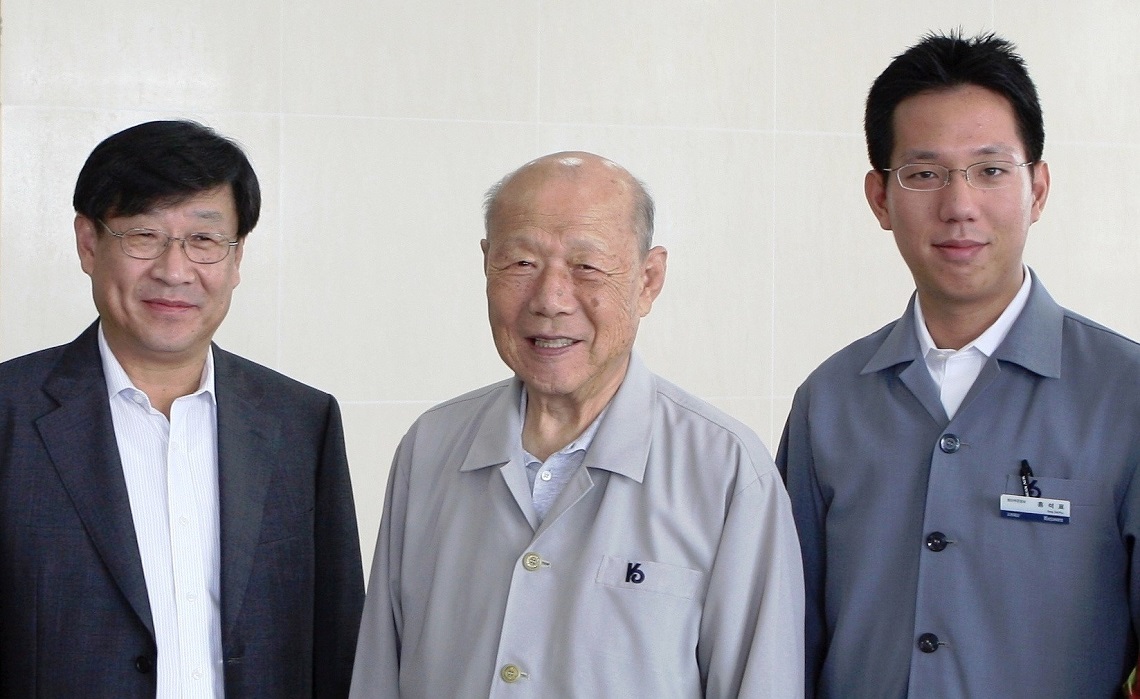

Suk-Cheon, Young-Chul and Scott Hong gather at KISWIRE’s Busan office on a sweltering late summer day. Outside, on the site of the relocated Sooyoung factory, construction has begun on the company’s new headquarters, residential education center, and wire museum, all to be powered by three forms of renewable energy. Always looking forward, even in celebrating the past.

As the three men recount stories, consider accomplishments and ponder the future, the family pride is obvious—albeit tempered by humility. It’s well-earned. Three generations, connected by steel wire and the honest hard work that makes it, have built a company that is the envy of its industry, and an emblem of Korea’s resilient economic growth.

“We don’t necessarily have to be the biggest,” says Chairman Young-Chul Hong. “We want to be the best—most efficient, highest quality product, most satisfied customers, happiest employees. That’s what we’re aiming for.”

“And look to new product lines,” Scott adds, “diversify within our core line of expertise.”

“If we can reach these goals,” says Honorary Chairman Suk-Cheon Hong, “I think we will also become the biggest.”

Like grandfather, like father, like son.

“I’m fully satisfied with the company today, and its growth under my son’s leadership,” concludes the Honorary Chairman. “And I have full faith in this promising young grandson of mine.”

That grandson puts his faith in tradition. “I’m really happy that we’re all in this business together,” Scott says. “It’s tradition. I don’t see it as pressure, but rather a sharing of wisdom that is essential to advancing this company and this family. In a way, I’ve been preparing my whole life for this.”